A tale of three leaf models

The temperature of a plant’s leaves is a really interesting parameter. Temperature is influenced by both things happening inside the plant (photosynthesis, respiration, etc.) and also the environment the plant is in (air temperature, humidity, downwelling radiation, etc.). In general, under constant environmental conditions a warmer plant is unhappier than a cooler plant. Healthy leaves are photosynthesizing and evaporating water. Evaporating water cools the leaf, so if that process is disrupted for some reason the leaf will warm up. If we measure a leaf’s temperature, we can have a general idea of whether the plant is happily photosynthesizing or experiencing some form of stress. But, here’s the problem. Outside of the laboratory, environmental conditions are never constant.

When we measure a leaf’s temperature, how do we know whether that temperature is a good or a bad sign in that plant’s environment? A paper just came out that uses flux tower data to answer this question, and I think the authors’ approach is worth focusing on. To understand why, let’s take a look at models of leaf temperature through time.

Approach 1: Empirical models

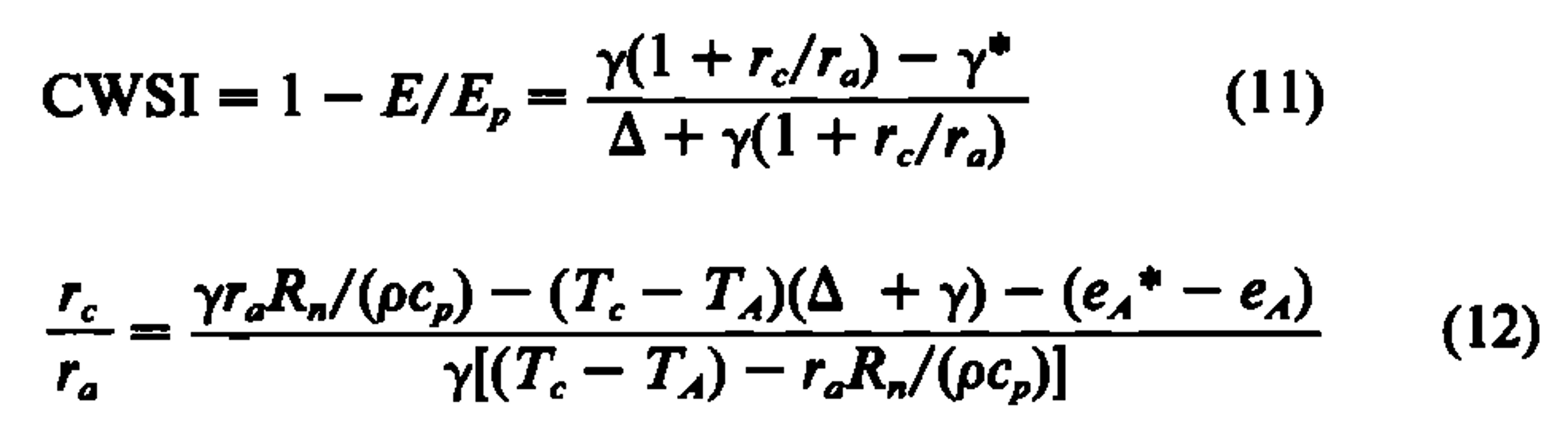

The use of leaf temperature to model plants finds its roots in the 1980s. A group from the US Water Conservation Laboratory used the Penman-Monteith equation, an evapotranspiration model, to model water stress with leaf temperature. They developed an index called the crop water stress index (CWSI). Conceptually, the CWSI compared how much a leaf transpired compared to the maximum rate under the observed conditions.

Unfortunately, the analytical version of this index was a little gnarly to calculate.

So, the same year that the original CWSI paper was published, the same group came out with an empirical version that could be deployed in crop fields.

This new version of the CWSI was much easier to use, but required more setup. Instead of modeling the maximum transpiration rate, the empirical CWSI compared the temperature of a given leaf to well-watered and water-stressed control plants. If the temperature of your field was closer to the water-stressed control, you could say that your crops are water stressed. And, if the temperature of the field was close to the well-watered control, you wcould say that your crops are not water stressed.

The empirical CWSI has since been studied in dozens of plants with consistent success. Produce you eat may have been irrigated using guidance from a CWSI monitoring system. But, what if we work in a natural system where we cannot manipulate some plants to be stressed and others well-watered? In this case, we again have to turn to modeling.

Approach 2: Leaf-level model

The second major approach to modeling leaf temperature is to consider the physics of heat transfer at the leaf level. These models generally assume energy balance, that is, the amount of energy entering a leaf is the same as the amount of energy exiting a leaf. The model will use a series of equations to describe heat transfer in the leaf which can then be solved for leaf temperature.

A recent example of such an energy balance model is described in Okajima et al. (2012) and implemented in the R package tealeaves. I’ve also written a Shiny application to interact with the model.

Although energy balance models have a sound physical basis, they require parameters that are difficult to measure. For example, the model implemented in tealeaves represents the transpiration rate of the leaf through two parameters: stomatal conductance and cuticular conductance. If I want to know the temperature of a non-transpiring leaf, I can simply set both conductances to zero. But, what about a rapidly transpiring leaf? It isn’t clear how one would model this scenario. Set both conductances to infinity? Look up reasonable values in the literature?

Another drawback is that the mathematical complexity of energy balance models makes them slow to calculate. Leaf temperature appears in multiple places in the model, so one must solve the system numerically. For lightweight modeling work this doesn’t matter too much. But, if I want to implement an energy balance model with remote sensing data, I quickly run into scaling issues.

Approach 3: Flux tower model

A recent paper in Agricultural and Forest Meteorology presents an energy balance model derived from flux tower data. This model doesn’t have to be solved numerically (mostly), provides clear endmembers to represent stressed and unstressed leaves, and so far has excellent correspondence with measured leaf temperatures.

Here is the model’s parameterization of leaf temperature.

\[T_L = T_a + \frac{Q_a r_H}{k \rho c_p}(1-f_E)\]\(T_L\) is leaf temperature, \(T_a\) is air temperature, \(Q_a\) is net radiation, \(r_H\) is resistance to sensible heat transfer, \(k\) is the sidedness of the leaf, \(\rho\) is air density, \(c_p\) is heat capacity, and \(f_E\) is the “evaporative fraction”, or the proportion of \(Q_a\) that is dissipated by transpiration.

The first thing to note is that this is very easy to calculate from flux tower data. \(Q_a\) corresponds to NETRAD in Ameriflux data products, and the resistance, density, and heat capacity parameters are easily approximated from meteorological data. We don’t have to consider leaf-level characteristics because these are all buried in the flux measurements that go into calculating NETRAD. I was able to reimplement this model in R and reproduce figures in the paper in about a day.

The more important note is that \(f_E\) gives us a clear way to model stressed and unstressed plants with very few assumptions about leaf characteristics. When \(f_E = 0\), leaves are not transpiring at all. When \(f_E = 1\), leaves are transpiring about as fast as energy balance allows. One caveat is that if we manipulate \(f_E\), we have to calculate \(Q_a\) manually and end up solving the model numerically.

The authors tested their model by comparing the modeled leaf temperature with measured canopy temperature from the flux tower (T_CANOPY in Ameriflux). The authors report good correspondence in their study sites in Arizona, which appear to only have one radiometer measuring canopy temperature on each tower.

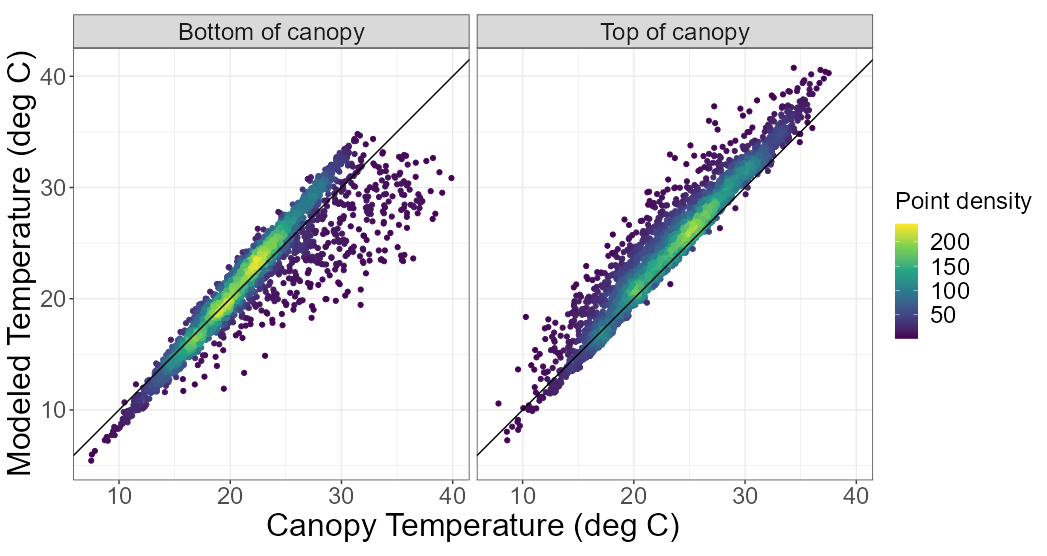

I was curious how this model would perform somewhere with a more complex canopy. So, I applied this model to flux data from Wind River Experimental Forest (US-xWR). This flux tower is great because it has six radiometers measuring canopy temperature along a vertical profile. If we recreate Figure 2 from the paper on data from the top and bottom of Wind River’s canopy, we also get pretty good correspondence.

It seems like this approach overestimates leaf temperature in the upper canopy, but underestimates in the lower canopy. Overall, not bad at all. Since the NETRAD measurements come from the top of the canopy, it makes sense that we would have a slightly better model there. Also, this is a very back-of-the-envelope plot. For example, I’m not filtering to observations where the latent heat flux is transpiration-only.

In summary, I think this new model for flux tower data is super cool. It works out of the box with flux tower data, is easy to calculate, lends itself well to modeling stressed plants, and seems to perform well in different environments. Bravo to the original authors!