Geomorphons in Earth Engine

Let’s say I have an elevation map of a landscape, and I want to find all the hills. One way I might do this is by looking at each cell, and comparing its elevation with its neighbors. If the cell is higher up than its neighbors, it’s a hill. You can extend this idea to other landforms too. If the cell is lower than its neighbors, it’s a sink. If some cells are higher and others are lower, the cell might be on a hill. The core idea here is to classify each cell in a landscape by its relationship to its neighbors.

Geomorphons are an approach to exhaustively quantify every possible cell-neighbor relationship. In an elevation raster, consider a cell and its 8 neighbors. For each neighbor, encode the sign of the difference between the cell and its neighbor. We then have a string of 8 values, -1, 0, or 1, for each cell. The cell’s “geomorphon” is a ternary code made from the string.

Looking at these codes, we can quickly see how they are related to landform type. If all neighbors are higher than the central cell, the geomorphon will just be -1 8 times. If all neighbors are shorter, then the string will be 1 8 times. A slope will have a mixture of 1, 0, and -1. Flat spots will have more 0 than 1 or -1.

With 8 ternary digits, we have \(3^8\) = 6,561 possible geomorphons. Not all of these are unique. By rotating or reflecting geomorphons, we can show that many of them are exactly the same. For example, consider the geomorphon 10000000. One neighbor lower than the central cell, then all others at the same elevation. Now consider 01000000. Although the two strings are unique, they are semantically equivalent. Even if 6,561 geomorphons are possible, we definitely want to merge some codes together.

In a later paper, the same authors describe how to merge geomorphons into 10 possible classes based off of the number of 1, or -1 digits in the string. WhiteboxTools implements this approach, and I was curious if you can do it in Earth Engine too. Turns out, you can!

The key idea here is to use kernel convolutions to compare a cell of an elevation raster with a neighboring cell. For example, say we want to find the sign of the difference between a cell \(x\) and its top-left neighbor, \(a\). To do so, we use a convolution to shift \(a\) into the position \(x\) was in.

\[\begin{bmatrix} a & - & - \\ - & x & - \\ - & - & - \end{bmatrix} * \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} - & - & - \\ - & a & - \\ - & - & - \end{bmatrix}\]Then we can easily subtract the convolved elevation raster from the original elevation raster and take the sign - that’s the first digit of the geomorphon. Repeat this process with the kernel rotated for the other neighbors and we get the ternary code. Then, count up the number of positive and negative signs and use a lookup table (Fig. 4 in the linked paper) to get the final landform classification.

I’ve written an example script here for the elevation image from the SRTM mission. But, this approach is image-agnostic and should work on whatever elevation model you have.

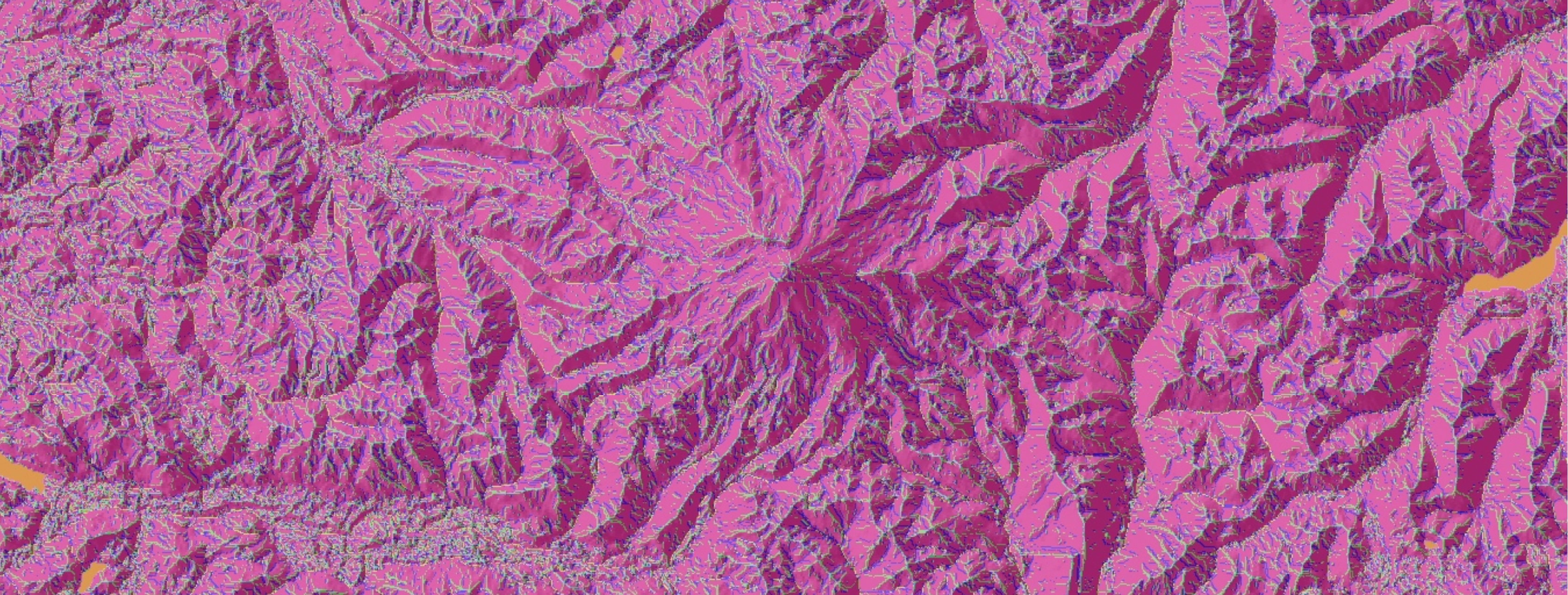

Below is an example of the geomorphon classification near Mt. Rainier. Orange is flat cells, pink is ridges, and light green is ridges. When overlaid with a hillshade, you can see how the classifications correspond to real life features.